Elizabeth Jaeger in Art in America

The Body Politic: A Conversation with Elizabeth Jaeger

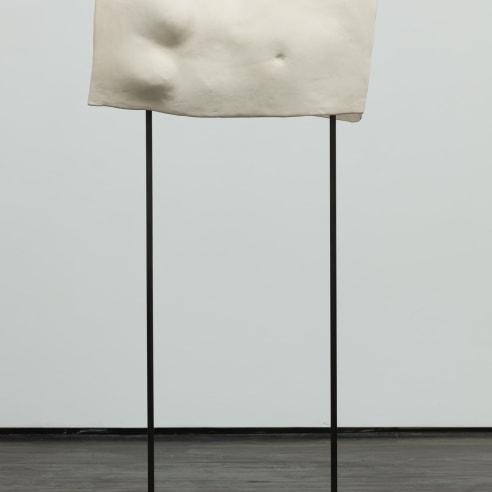

Elizabeth Jaeger is known for evocative figurative sculptures that manipulate traditional social and art historical tropes about the female body. As William S. Smith wrote in the First Look column in A.i.A.'s September 2014 issue, the artist "exploits the familiarity of the human body, orchestrating nuanced plays of estrangement that recall the work of Robert Gober and Kiki Smith." In the last few years, Jaeger has moved away from figuration per se to more stylized sculptural forms that only suggest the female body, thus literalizing objectification in order to subvert misogynistic associations obliquely and profoundly.

Jaeger spent much of the summer making abstract silk paintings in upstate New York as a resident at the Shandaken Project residency at Storm King Art Center. Inspired by the lush landscape of her surroundings, these paintings—composed of layers of dye, applied in washes, and intended to be used in set designs for a friend's band—permit the Brooklyn-based artist to transfer her sculptural dexterity to two dimensions while escaping the pressures of producing work for display in galleries.

This doesn't mean that Jaeger has withdrawn from the art world. Her sculpture is currently on view in the group shows "Sticky Fingers," at Arsenal Contemporary, New York, through September 6; and "Dreamers Awake," an all-women exhibition exploring the enduring influence of Surrealism, at White Cube, London, through September 17. Later this year, she will participate in group shows at Klemm's and Galerie Rolando Anselmi, both in Berlin, and Galleria Zero in Milan. I caught up with the busy artist on August 1, shortly after her return to the city from Storm King, and we spoke about the pleasures and pitfalls of figuration, artist's books as sculpture, and letting works mutate over time.

JULIA WOLKOFF Have you had a productive summer so far? Has returning to New York been challenging?

ELIZABETH JAEGER I've only been back for twenty-four hours, but there's a really different relationship to time here. When I first arrived upstate, the days seemed really long, and I wondered how I would make it to eight o'clock. Then as I got more comfortable doing my own things, the days became really short. In New York, they also feel extremely fast. It's suddenly five o'clock and all I've done is take the train somewhere.

WOLKOFF What have you been up to since you were featured in First Look? How has your practice evolved since 2014?

JAEGER The work featured in that issue [Serving Vessels, 2013] was like a bridge to my more recent work. I'm thinking now about things that can have the same emotional or conceptual capacity as the figure without evoking a specific type of person.

WOLKOFF One recurring form in your work is the vessel, like an amphora, or something flatter. Your March 2016 show at Jack Hanley in New York was an interesting progression from Serving Vessels, which consists of a bewigged black ceramic female figure reclining on a glass shelf that's laden with rough black cups, bowls, and other ceramic objects. These newer sculptures only allude to torsos, and transform them into objects that recall the shape of a pommel horse. How would you articulate the connection between a vessel and the body?

JAEGER It's common to talk about women as vessels, which is extremely sexist. For that show I was thinking about this issue and about the odalisque as something that started as a concubine or sex slave but has now become something beautiful in art. I wanted to instill the female form with a more dangerous meaning. Women are too often treated like receptacles for other people or other issues, like scapegoats.

I'm not interested in the vessel because it's figurative. There's just so much you can do with the vessel that departs from vessel-ness. The vessel has an innate utility to it. I also think a lot about turning something over twice. It's the same thing it was before, but it's gone through something; it's off by two degrees. I try to challenge people's preconceptions of what a certain shape should do, or how it should act with other things. People are hard-wired to perceive faces in anything. Instead of making a figure, I connote one.

WOLKOFF Have you become more uncomfortable with figuration?

JAEGER The first time I showed my work in New York was in 2015 at the NADA art fair. The gallerists told me that Jerry Saltz had walked by and really liked the work. I have a photo of him sitting between the legs of this nude figure. Apparently, according to the booth attendants, he asked, "Is this artist a man or a woman?" They said, "A woman," and his response was, "She's brave." What the fuck does that mean? There's this idea that a woman artist who creates nudes is absolved of responsibility, and I'm really against that. It's just as objectifying as it is when a man does it.

There's also this idea that men are raised differently from women, but we're actually all raised similarly if not the same, in the sense of our exposure to oppressive and sexual imagery. We're all taking it in. As an artist, I'm becoming more critical of myself for making work based on that upbringing, either in how I limit myself because of my gender or how I depict my gender in a crude or oversexualized manner.

WOLKOFF Many conversations about women's issues, especially in the political sphere, are viewed through the lens of reproductive rights, which has to do with the body. But there's much more to how we operate in the world.

JAEGER It can be very limiting. I enjoy seeing works that feature nude, liberated female bodies, but at the same time my feelings are complicated. Maybe the work is not really liberated. Lots of artists are still defining womanhood by a nude body, usually a young one.

Meriem Bennani just posted a music video to Instagram today. It features women in hijabs. One of them is dancing, another is riding a horse, yet it doesn't feel objectifying at all. The lyrics are in Arabic, and I can't understand what's happening. So maybe I'm wrong, but their presence is so stoic and beautiful and powerful and elegant. A lot of women talk about the hijab as being liberating. Some disagree. But it was interesting to see that video walk that line.

WOLKOFF You run a publishing imprint called Peradam with photographer Sam Cate-Gumpert. What are you working on now? What do you enjoy about making artist's books?

JAEGER Mostly the collaboration. Sam is one of my best friends. Peradam serves as a means to continually keep conversations going between artists, and to bring people in to a community.

WOLKOFF You've published your own books, including a flip-book. How does your approach to this differ from your sculptural practice?

JAEGER I think about many of the books as sculptures, about their usability, and how they move. The flip-book that you're referring to is designed like a romance novel, in terms of size and composition. Then when you open it, you have to readjust to a flip-book format. It's less about the content on the page than the experience of handling the physical book. I'd have to say most of Peradam's books have that focus.

WOLKOFF Your work is included in a couple group shows up now, and you also have several exhibitions in the works. How do you negotiate this accelerated pace of exhibiting?

JAEGER Because of the New York real estate situation, I used to make work only when I was invited to participate in a show. Otherwise, where the hell are you going to store your stuff? For a long time, I felt like I was always playing catch-up, always starting the work for the next show just a few months before it opened. Now I'm at a place in my career where I can make whatever work I want to and then someone will select some pieces to show. It can be hard, because I have to become comfortable with things not being site-specific. This has actually come to make more sense to me, since a gallery is like a holding place for work before it goes somewhere else. Art moves more frequently than it ever has before, so making something site-specific is getting harder and harder.

WOLKOFF And a little anachronistic?

JAEGER Exactly. After doing the group show "Mirror Cells" at the Whitney Museum last year—all of that work was made for the show—I began to just make things and let them sit in my studio, allowing myself to warm up to or cool off to them and make changes. It's been a huge development.

WOLKOFF Do you find that you revise more?

JAEGER Or things will grow. Before, I'd make something and it would go in a show and come back and maybe I'd revise it. Now I'll look at something for two months and then build something that goes with it. Things change when they're around for a long time. And that's great! They become deeper and more layered.