Jess Johnson in Artforum

Chloe Wyma on Jess Johnson

November, 2017 Print Issue

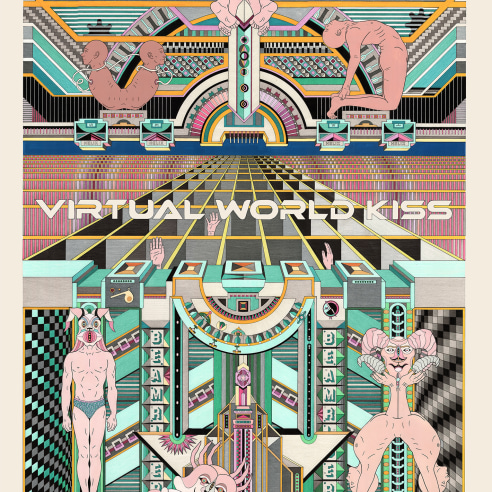

“What is being described here is in fact a machine,” Roland Barthes wrote of the Marquis de Sade’s pornographic scenarios, “ . . . a meticulous clockwork, whose function is to connect the sexual discharges.” While there is little if any, sex in Jess Johnson’s meticulous drawings, rendered in pen, marker, and gouache on paper, there’s more than a hint of the structuralist Sade in her unindividuated, compliant nudes, which function as fungible units in a fabulous and brutal visual grammar. Divested of sexual or psychological characteristics, they are arranged in esoteric diagrams in complex, multiplanar spaces teeming with crypto-Masonic symbols, arcade colors, and tessellated surfaces. Often, these dumb, desubjectivized bodies perform rites of supplication to various animal-headed gods and giant insects.

Born in 1979 in Tauranga, New Zealand, Johnson (now based in New York) is a self-described product of ’80s and ’90s comic books, horror movies, video games, and science fiction. Russell Hoban’s postnuclear dystopic novel Riddley Walker (1980) and the druggy techno-sensualism of the New Age shaman Terence McKenna (whom Timothy Leary himself called the “Timothy Leary of the ’90s”) were major influences. Johnson’s first New York solo show introduced viewers to her elaborate and hermetic visual cosmology, which collapses elements of a pharaonic past with those of an abstract, cybernetic future.

In Wurming Way, 2016, a massive green worm that plays a central role in Johnson’s personal demonography becomes a grotesque Ouroboros, its colonic form twisted into a figure eight against a ground of pink bodies that swirl in Brownian motion. In Transkin Simulator, 2017, a column of nudes in brown, tan, and pink floats against a checkerboard plane that recedes into outer space, bounded by a glittering skyline and a totem pole of horned and bat-faced gods. Impossible acrobatics continue in Milxyz Wae, 2017, where a human figure and fifteen masked deities circumambulate a tentacle-covered nucleus in front of a neon ziggurat. Likewise, in the animation Whilst in Genuflect, 2017, made in collaboration with video artist Simon Ward, seven figures, lying on their backs with outstretched knees, contort into a stepped pyramid crowned by a serpent. A subterranean network of wires or entrails emanates from the illuminated disco floor, sprouting from two of the figures’ mouths. In Worldken, 2017, human faces and extremities accumulate in cosmic pinwheels around genital-faced idols. More naked people—tendrils blindfolding their eyes—float limply in space, while more still are packed inside the composition’s infernal bottom register, supporting text spelling out FLESH INTERFACE EUTOPIA.

“Most of what we look at every day has been designed digitally by a machine somewhere,” Johnson commented in a 2015 interview. “It’s like all our images have been fed through a machine at some point and regurgitated back to us. I’m just regurgitating it back to them,” she said of her traditional drawing methods. “It’s quite perverted, I guess.” The intercourse of media and form became even more perverse—Sadean perhaps—in four looping digital animations, arranged in an octagon in the center of the gallery. Made in collaboration with Ward and composer Andrew Clarke, each translates scans of one of Johnson’s drawings into its torpid, unnerving double, the affectless bodies endowed with three-dimensional contour and basic motility. In the virtual reality animation Ixian Gate, 2015, the viewer, donning an Oculus Rift headset, momentarily forgets her body and surrenders to Johnson’s world, replete with flying worm monsters, fantastic temple architecture, and depthless voids. What is this place, and what meaning does it make beyond its exceptionally articulate, self-reflexive arcana? “The world doesn’t have a name,” Johnson said. “I think it might actually kill it to name it.”

—Chloe Wyma